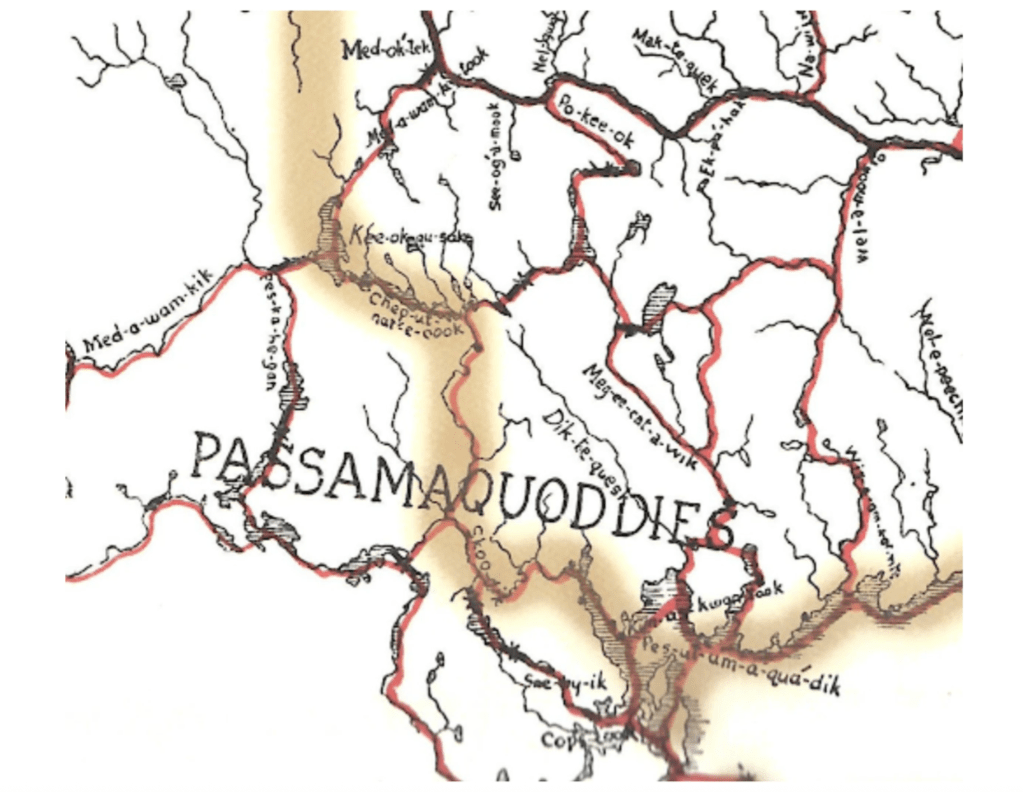

Indigenous Mi’kmaq, Wəlastəkokewiyik, Peskotomuhkatiyik, & Pαnawάhpskewəyak Canoe & Portage Routes

Still referenced today for its navigational accuracy, this 1899 map was created collaboratively by W.F. Ganong and numerous, uncredited, Indigenous contributors. The map is an incredible window into the complex transporation system of Wabanaki societies. In addition, it is a window from the perspective of Western cartography (Western approaches to map making). The map was drawn by a white Canadian botanist and cartographer who spoke Peskotomuhkati and traveled widely in the bush with Wabanaki guides.

In the zoomed-in portion below, note the anglicized versions of Peskotomuhkati river names written by Ganong. A snapshot in time. The creolization (creative mixing) of the Wabanaki and English languages was in mid-process, and this map is a prime example.

Thousands of years before, the Peskotomuhkati developed their visual language to navigate the vast water network of their homeland. It was, and still is, a cartography characterized by a relationship with the place, using physically descriptive place names tied to stories, and the creative sizing of different points on the map to communicate importance, danger, or difficulty of passage. A map for berry picking would differ from a map for fishing. Maps can be perceived as powerful storytelling tools alongside their navigational use.

The example above looks very different from Western map languages, and yet the European’s mapping methods were notoriously helpless when attempting to navigate through Peskotomuhkatikuk and the wider Dawnland territory.

Imagine: the Wabanki map looks “normal” to your eyes, and the Ganong map looks like an alien view, too high in the sky to be of any real use.

Of course both are valuable because both bring us closer to Peskotomuhkatikuk in different ways. The Ganong map is directly indebted to the Wabanki map and to the Wabanaki people who helped create it. Back then, there was more than one way to draw a map.

There still is.